Imagine going for an operation to replace your diseased trachea — the surgeons have a small printer in the operating theater and, using your own previously harvested cells, they print you a new windpipe and transplant it directly into your body.

Such a scenario could be realized within the next 5-10 years, according to KAUST bioengineer Charlotte Hauser, who works at the forefront of 3D bioprinting research.

The most innovative aspects of her research are the material she uses for the scaffold — the interlocking structure of the body part — and the robotic printer developed in her lab, which ensures extremely accurate and consistent results.

Bioprinting is used to create tissue, organs or other body structures in the presence of cells. The process requires a scaffold to mimic the structure of the target body part and a gel that contains the human cells or proteins to promote their growth. Unlike many groups who use nonnatural polymers that have no resemblance to natural fibers, Hauser has developed a biomimetic collagen that closely resembles human collagen, the body’s connective tissue, to use as a scaffold for all kinds of grafting with tissues. She describes it as a natural synthetic material.

As well as the tracheal replacement project, Hauser and her team work closely with hospitals in Saudi Arabia for drug screening using models for diseases, such as colon cancer and leukemia.

By recreating a 3D structure of a tumor in the lab, they can screen to determine what drug or cocktail of drugs is most effective to reduce or even destroy the tumor.

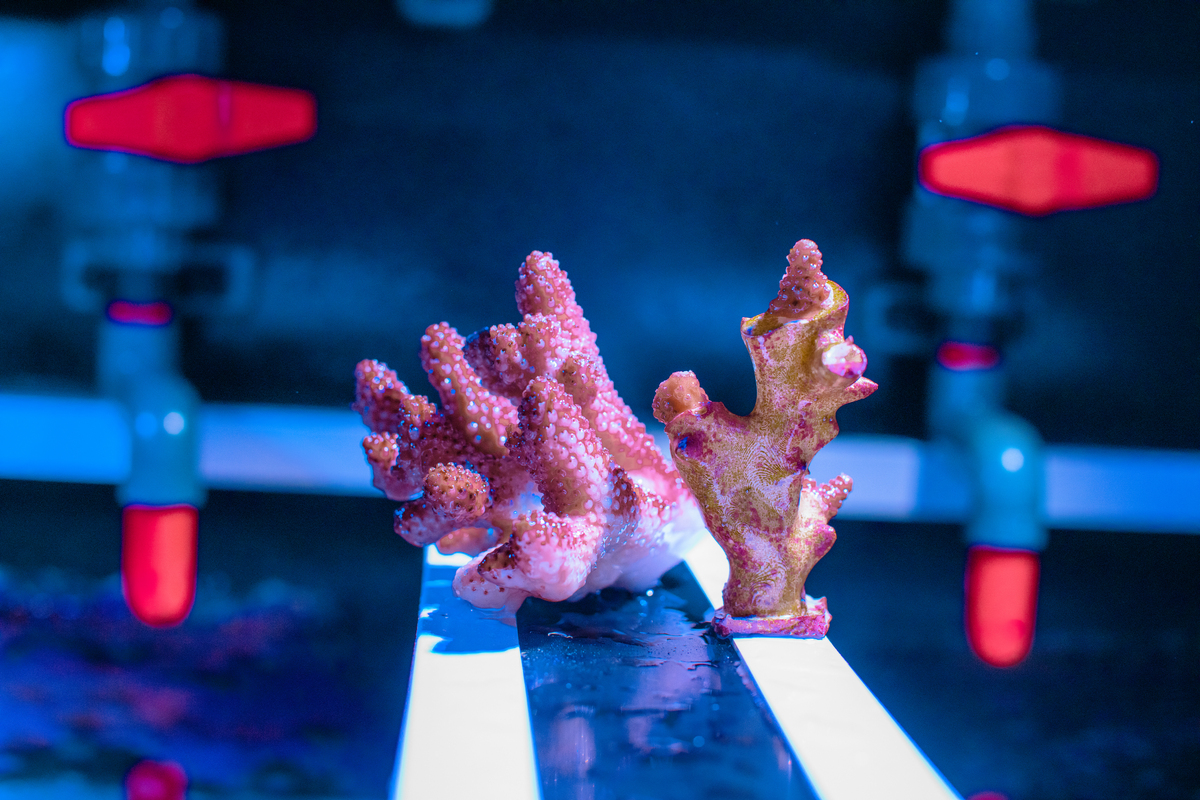

Coral regeneration

Bioprinting also has environmental applications. Hauser and her team are collaborating on coral reef restoration with Carlos Duarte and other colleagues in KAUST’s Red Sea Research Center. She is also involved in Saudi Arabia’s NEOM coral restoration project, which will include the world’s largest coral nursery.

Coral skeletons are made of calcium carbonate. Hauser’s team has developed a calcium carbonate photo-initiated ink, which is a mixture of resin and calcium carbonate.

“With all my materials, I’m trying to ensure that they are decomposable, sustainable and ecofriendly for a more biocompatible world.”

“The problem with other materials used as substrates, such as concrete and metals or even ceramic tiles, is that the substrate itself becomes waste,” she explains. “With all my materials, I’m trying to ensure that they are decomposable, sustainable and ecofriendly for a more biocompatible world.”

Her team is currently performing proof-of-concept studies with this material in seawater tanks. However, for large-scale reef restoration projects, they are printing silicone molds that are much quicker to print and will enable them to scale up the project.

Hauser says the main challenges lie in the technology itself and sourcing the materials, such as the customized bio inks and scaffold material, for example. For her, the goal is always to come as close to nature as possible in tissue engineering, in terms of devising the best biomaterials to use in scaffolds and learning how to grow organ-specific cells outside the body while keeping them alive.

She believes that the future lies with in-vivo printing, such as a printer in an operating theater that uses the patient’s own cells and that is easy enough to use by surgeons. “The translation is already happening.”